Why the late Shah Remains Central to Iran's Political Debate?

For many Iranians, the Shah is more than just a toppled monarch; he symbolises a time of potential and progress.

A recent article on the BBC World Service Persian website has sparked a heated debate in the Iranian political sphere. Written by Dariush Karimi, a BBC Persian editor, the article drew a controversial comparison between Asma al-Assad, the wife of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, and Empress Farah Pahlavi, the wife of Iran’s late Shah (King).

The comparison was quickly criticized by many Iranians, both inside and outside the country, who accused the BBC of presenting a biased and misleading narrative. The juxtaposition of a brutal Syrian regime—accused of causing the deaths of over 600,000 people—with the legacy of Iran’s last monarch and his wife was seen by critics as problematic and politically charged.

The controversy centred around what many perceived as an attempt to tarnish the Shah's image by associating him with the Assad regime. Critics reminded BBC Persian that, despite having military forces capable of quelling the 1979 protests, the Shah chose exile to prevent further bloodshed—an act of restraint that contrasts sharply with the violent repression employed by other regimes in the region.

Furthermore, Empress Farah, who made significant contributions to advancing women's rights, social reforms, and Iranian cultural representation on the global stage, was defended by social media users for her role in promoting social and cultural changes that benefitted Iran’s women, children, and marginalised communities.

But why do many Iranian post-revolution generations defend King Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah?

"King of Kings, May Your Soul Rest in Peace"

The phrase "King of Kings, May Your Soul Rest in Peace" became a main slogan during Iran’s 2022 “Women, Life, Freedom” protests. These protests, driven largely by Iranian Gen Z, were sparked by the tragic death of Mahsa Amini, a 21-year-old woman allegedly killed by the Islamic Republic's morality police for not adhering to the country's strict hijab laws.

However, the protests were not only about Amini’s death but also reflected a growing frustration with the regime's interference in personal lives, the country’s failing economy, and the disconnection between the ruling authorities and the Iranian people. Despite the regime’s attempts to control the narrative, the younger generation in Iran is increasingly aware of their desire for a “normal life,” one free from the ideological constraints of the current regime. Iranian youth, often relying on the internet and international satellite TV to access information, envision a future that mirrors the prosperity and social freedoms Iran once experienced before the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The Revolution of Archive

Despite the Iranian regime's efforts to control the narrative through state-backed propaganda, the younger generation has increasingly turned to alternative sources of information to learn about their country’s past.

This shift can be traced back to the 1980s, when access to foreign media was severely restricted. Even then, many Iranians found ways to access forbidden content, such as through the illegal import of VHS tapes.

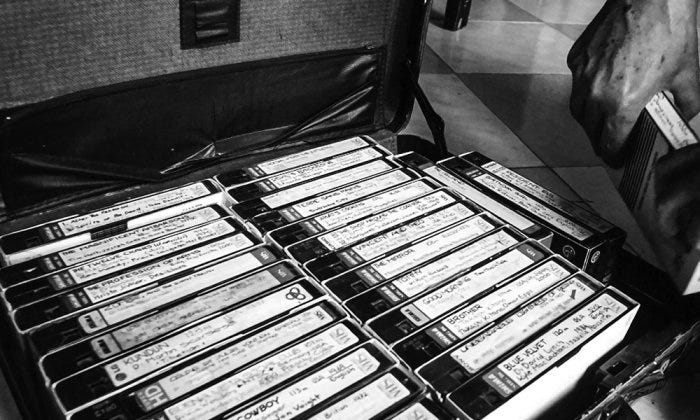

Owning a video player during that time could lead to severe punishment, including lashes. But, like many other restrictions, this one was also circumvented by the people, including my family. With a video player at home, we had the freedom to choose what we watched on our colour television. A family friend introduced us to a man who ran an unusual business. Every Saturday, he would arrive at our house carrying a Samsonite bag filled with forbidden videotapes. When he opened the bag, it revealed two rows of VHS tapes. On the right were Iranian films and TV shows from before the Islamic Revolution, along with music programs featuring Iranian artists who had fled to Los Angeles. The left row contained contemporary English-language films, although my mother always insisted on including one English film in the selection. The next week, the man we called “Mr. Filmi” would return to swap the old tapes for new ones. We were forbidden to discuss these films or videos with anyone outside the house.

These films and access to banned content had a profound impact on my generation. From as young as four or five, we were exposed to pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema, pop music from the Shah's era, documentaries about life in Iran before the Islamic Revolution, pop culture, and even concerts held in Iran. I’ll never forget watching a performance by Frank Sinatra, who visited Iran in the '70s for a concert. This informal education played a crucial role in shaping our generation’s identity. The content was smuggled out of government archives and copied illegally, serving as a window into a world we could not openly experience.

Today, Iranian Gen Z has even more access to international content, including materials from Iran's pre-revolutionary period. In 2011, a vast trove of pre-revolutionary TV footage was smuggled out of Iran’s national archives and began circulating online. Persian-language satellite channels, like London based Manoto TV, began to broadcast documentaries made of the archival content, which included interviews with figures such as Queen Farah. These broadcasts offered a stark contrast to the official narrative propagated by the Islamic regime.

The reemergence of these archival materials helped fuel the anti-regime sentiments that have surfaced in protests since 2018. Protestors began chanting slogans in support of the late Shah and his father, showing that the legacy of the Pahlavi era continues to inspire a significant portion of the population.

"Zamaneh Shah" – The Shah’s Era

The phrase “Zamaneh Shah,” meaning "The Shah’s Era," continues to resonate across generations of Iranians. During the Shah’s 37-year rule, the country transitioned from being part of the “Third World” to becoming a regional powerhouse.

Under the Shah's leadership, Iran experienced an unprecedented economic boom. National income increased by 423 times, urbanization flourished, and the country made major strides in industrial and military development. By 1977, Iran had the fifth-strongest military in the world. The Shah’s focus on defense, infrastructure, and education resulted in significant improvements across various sectors, making Iran one of the fastest-growing economies in both the developing and developed worlds.

Queen Farah: A Symbol of Women's Rights and Social Reform

Empress (Shahbanoo) Farah Pahlavi, who was controversially compared to Asma al-Assad by BBC Persian, was an architect turned queen who became an advocate for social change in Iran. After marrying the Shah in 1960, she became an influential figure, championing women’s rights, children’s welfare, and the rights of marginalized groups. Through the Farah Pahlavi Foundation, she supported numerous cultural institutions, including museums and art centers, and funded a wide range of charitable causes.

Her commitment to education was evident in her efforts to improve literacy, particularly among children, by establishing libraries across urban and rural areas. Using her architectural expertise, Empress Farah also helped preserve Iran’s cultural heritage by restoring historic buildings and improving urban planning, particularly in Tehran’s southern districts.

As Iran’s first crowned female sovereign and the first woman to be crowned in the Muslim world, Empress Farah broke significant barriers for women’s rights and political representation. Empress Farah, Also known as Shahbanoo (Persian for crowned queen) of Iran, served as regent in the event of the Shah’s death—a groundbreaking role in Iranian history. While Iran under the Shah was not a democracy in the modern sense, it was far ahead of many other countries, both regionally and globally, in terms of economic and social progress.

The Lasting Legacy of the Shah and Shahbanoo Farah

For many Iranians, the Shah is more than just a toppled monarch; he symbolises a time of potential and progress—a time when Iran was striving to be a prosperous, modern nation with a strong global presence. Under his rule, the economy thrived, women were granted equal rights, music and dance were celebrated, and Iranian citizens could travel freely across Europe. The Shah’s Iran was an ally of both the United States and Israel, and his regime is often remembered for fostering an era of stability, economic growth, and social reform.

This enduring legacy is why many Iranians view the BBC’s comparison between the Assad regime and the Pahlavi family as an attempt to undermine the memory of a more prosperous and hopeful time. Many perceive the BBC's approach as aligning with the Islamic regime's propaganda, rather than countering misinformation. When the BBC Persian Service draws parallels between the brutal Assad regime and Iran’s last monarch, it evokes a response from people who continue to associate the Shah’s era with progress, modernisation, and international respect.

For the younger generations, who have only heard about the Shah's reign, the past continues to shape their vision of a better future—a future where Iran is once again a proud, independent, and prosperous nation, free from the constraints of ideological tyranny.